Presentation

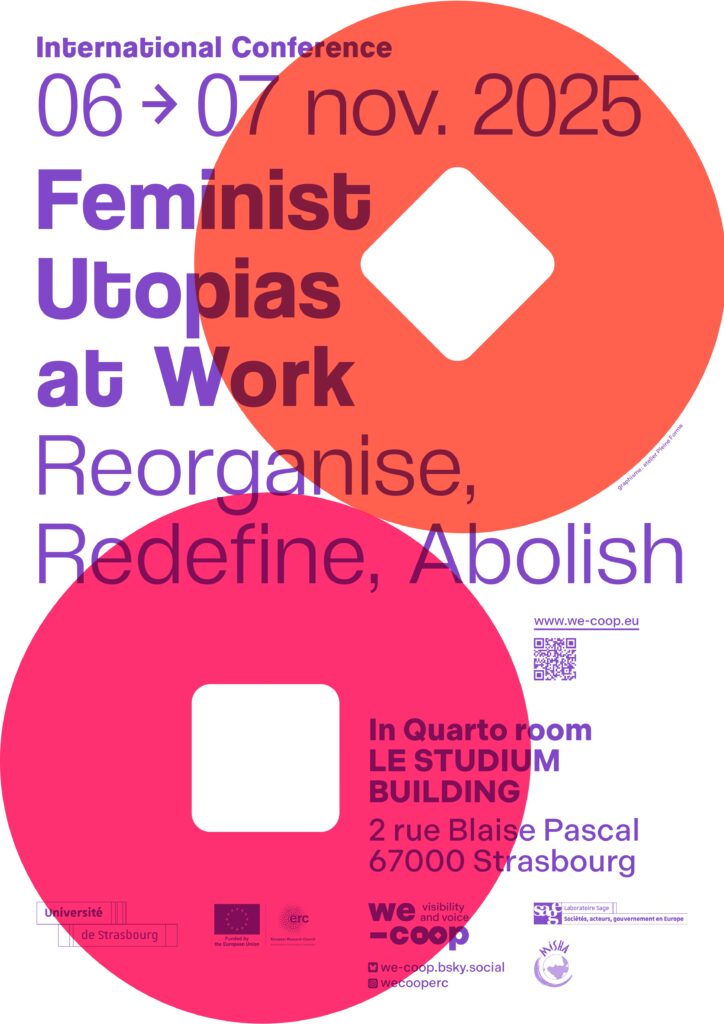

Feminist Utopias at Work

Reorganise, Redefine, Abolish

Thursday 6 and Friday 7 November 2025, 8:30 a.m.-6:00 p.m.

University of Strasbourg

In Quarto Room, Le Studium building

2 rue Blaise Pascal — Strasbourg, France

Directions

FREE ADMISSION AND OPEN TO ALL

In English and French, with simultaneous subtitles

The round table and the keynote were recorded !

> https://www.canalc2.tv/video/17034

Keynote Speaker:

Jessica Gordon-Nembhard, Professor of Community Justice and Social Economic Development, Department of Africana Studies, John Jay College, CUNY

Author of Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania University Press, 2014).

Guest Speakers Round Table:

Katia GENEL, Professeure de philosophie, Sophiapol, Université Paris Nanterre

Maud SIMONET, Directrice de recherche en sociologie au CNRS, Laboratoire IDHE.S Nanterre

Summary of the Conference:

Although feminist utopias have been the object of an important body of work especially in the literary field, the specific paradigm of labour within these experiments and imaginaries has received only limited attention.

The purpose of this conference is to explore to what extent and in what ways labour (both as a site of oppression and emancipation) serves as a paradigm in feminist utopia-building.

Utopias in the sphere of labour and their political content, which has sedimented in critical theory on work, are imprinted by the Western patrimony of utopian socialism. Although there has been radical, short-lived and often forgotten feminist influences as well as a matrimony now being highlighted, political constructions of “what labour could become” remain shaped by figures such as Fourier, Owen or Saint-Simon.

Feminist critiques have challenged androcentric definitions of labour, broadening the field to include alternative theoretical frameworks. Despite these critical claims, the historical development of capitalism – with its persistently gendered and racialised division of labour – can be considered as dystopian – a “bad place” – that has led some feminist thinkers to reject the idea of equality in such a context.

The conference will use utopia for its central function: “confronting the problem of power” through sidelining and introducing “a sense of doubt that shatters the obvious” (Ricoeur). While we firmly acknowledge the need for utopia in critical thinking, we also underline the importance of multiple approaches to emancipatory politics as a compass for utopia-building. As a result, we will accept understandings of utopia both as a reflexive tool for critique and as a heuristic tool for transformation.

Three complementary approaches to utopia-building will be considered: 1. Reorganise labour ; 2. Redefine labour ; 3. Abolish labour

Publication:

We are planning to publish the most relevant and developed papers as an open-access book on the theme of “Feminist Utopias at Work” with a renowned publisher.

Programme

Keynote

Building Co-Op Utopias: Black American Women Cooperators’ Journeys

Jessica GORDON-NEMBHARD

Professor of Community Justice and Social Economic Development, Department of Africana Studies, John Jay College, City University of New York (CUNY)

Thursday, 6 November 2025, 5:00 p.m. – 6:00 p.m.

In Quarto room, Le Studium building, University of Strasbourg

The video is also available on the University of Strasbourg channel: https://www.canalc2.tv/video/17034

****

Jessica GORDON-NEMBHARD

Professor of Community Justice and Social Economic Development, Department of Africana Studies, John Jay College, City University of New York (CUNY)

INVITED KEYNOTE SPEAKER

Author of Collective Courage : A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice (2014), and 2016 inductee into the U.S. Cooperative Hall of Fame, Jessica Gordon-Nembhard, Ph.D., is Professor of Community Justice and Social Economic Development, in the Department of Africana Studies, John Jay College, City University of NY.

Prof. Gordon-Nembhard is an internationally recognized and widely published political economist specializing in cooperative economics, community economic development, racial wealth inequality, solidarity economics, Black Political Economy, popular economic literacy, and community-based approaches to justice.

Recipient of numerous awards in social economics and cooperative studies, she is a member of the Cooperative Economics Council of NCBA/CLUSA ; the International Co-operative Alliance Committee on Co- operative Research ; a Faculty Fellow and Mentor with the Institute for the Study of Employee Ownership and Profit Sharing at Rutgers University School of Management and Labor Relations ; an affiliate scholar with the Centre for the Study of Co-operatives (University of Saskatchewan, Canada) ; and adjunct with the International Centre for Co-operative Management, Sobey School of Business, St. Mary’s University (Halifax, NS, Canada).

Jessica Gordon-Nembhard is also a past board member of the Association of Cooperative Educators ; a past fellow with the Center on Race and Wealth at Howard University ; and a member and past president of the National Economic Association.

She is the proud mother of Stephen and Susan, and the grandmother of Stephon, Hugo, Ismaél and Gisèle Nembhard.

Round Table

Où en sont les critiques féministes du travail ?

[Current Issues in Feminist Critiques of Labour]

With:

Katia GENEL, Professeure de philosophie, Sophiapol, Université Paris Nanterre

Maud SIMONET, Directrice de recherche en sociologie au CNRS, Laboratoire IDHE.S Nanterre

Moderation : Ada REICHHART, Professeure junior de sociologie, Université de Strasbourg

Friday 7 November, 4.45 p.m. – 6.00 p.m.

In Quarto room, Le Studium building

The video is also available on the University of Strasbourg channel: https://www.canalc2.tv/video/17035

* * * * *

Katia GENEL

Professeure de philosophie, Sophiapol, Université Paris Nanterre

GUEST SPEAKER

Katia Genel, Agrégée in Philosophy, completed a doctoral thesis on the question of authority in the Frankfurt School, carried out at the University of Rennes 1 in co-supervision with the Institut für Sozialforschung at Goethe University Frankfurt.

Deputy Director of the Centre Marc Bloch in Berlin from 2019 to 2022, her work focuses on German philosophy, social and political philosophy, notably critical theory, the epistemology of the social sciences, and more recently on feminist theories and philosophies of labour. Author of numerous articles and books, Katia Genel co-edited Le sujet du travail. Théorie critique, psychanalyse et politique (Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2022) and Croisements critiques. Actualité de l’École de Francfort (Le Bord de l’Eau, 2023).

Following an Habilitation à Diriger des Recherches in philosophy defended in 2024 entitled Approches critiques : du social au politique, et retour, she is publishing at the end of this year a work analysing the category of labeur, through the lens of feminist theories: L’oubli du labeur. Arendt et les théories féministes du travail (Klincksieck, October 2025).

* * * * *

Maud SIMONET

Directrice de recherche en sociologie au CNRS, Laboratoire IDHE.S Nanterre

GUEST SPEAKER

Inspired by feminist analyses of domestic labour, Maud Simonet’s work focuses on invisible or under-recognised forms of labour, particularly activities at the intersection of civic engagement and unpaid work.

Awarded the CNRS Bronze Medal in 2017, she is the author of numerous articles and books on volunteer work, civic engagement, and the concept of “workfare,” some of which adopt a comparative approach between France and the United States.

She has notably published Travail gratuit: la nouvelle exploitation? (Textuel, 2018) and L’imposture du travail. Désandrocentrer le travail pour l’émanciper (10/18, 2024), as well as, very recently, the results of a study on voluntary work during the Olympic Games: (In)volontaires aux JO: Récit d’un conflit du travail gratuit (Textuel, 2025).

In 2025, Maud Simonet co-organised a conference entitled “Current Issues in Reproductive Labour: Attacks and Responses” (our translation) and contributed to the establishment of a new international research network on reproductive labour.

Scientific Committee

We are delighted to count among the members of the Scientific Committee:

Sylvaine Bulle, Professor of Sociology, EHESS (Paris, France)

Pascale Devette, Professor of Political Science, Université de Montréal (Montréal, Canada)

Maria Ines Fernandez Alvarez, Adjoint Professor in Social Anthropology, Universidad de Buenos Aires (Argentina)

Jessica Gordon Nembhard, Professor of Community Justice and Social Economic Development, CUNY (New York, USA)

Bernard E. Harcourt, Professor of Law and Political Science, Columbia University (New York, USA)

Pascale Molinier, Professor of Social Psychology, Université Sorbonne Paris Nord (Paris, France)

David Paternotte, Professor of Sociology, Université Libre de Bruxelles (Brussels, Belgium)

Ada Reichhart, Researcher in Sociology, Université de Strasbourg (Strasbourg, France)

Maud Simonet, Research Director in Sociology, CNRS (France)

Organising Committee

Fanny Gouel, Research assistant at WE-COOP, graduate of EHESS

Ada Reichhart, Junior Professor of Sociology, Université de Strasbourg

Call for Papers

Feminist Utopias at Work

Reorganise, Redefine, Abolish

Although feminist utopias have been the object of an important body of work, especially in the literary field (Bartkowski, 1989; Halberstam, 2011; Jackson, 2020; Lillvis, 2017; Bammer, 1992; Peel, 2002; Vakoch, 2021), the specific paradigm of labour within these experiments and imaginaries has received only limited attention. The purpose of this conference is to explore to what extent and in what ways labour (both as a site of oppression and emancipation) serves as a paradigm in feminist utopia-building. We will consider utopias both as theories and social experiments, specifically through the modes of reorganisation, redefinition and abolition. In doing so, we wish to bring to the fore a “constellation” of breaches as a way of confronting, from feminist perspectives, the negative experience of labour under capitalism (Adorno, 1990).

By “feminist approaches”, we refer to reflexive research that analyses “gender as an organising structure and lived materiality that affects all gendered subjects in society”, and which especially relies on intersectionality as “a core political tool” to explore power relations in their diversity (Kiguwa, 2019; Collins, 2019). This conference aims to explore feminist utopia-building, considering specific struggles, debates and oppositions that arise from the multiplicity of power relations within the gender order, including (but not limited to) race, ethnicity, sexuality, class, disability and age, and bringing together marginalized perspectives and experiences of labour specifically.

Utopias in the sphere of labour and their political content, which has sedimented in critical theory on work, are imprinted by the Western patrimony of utopian socialism (Abensour, 2013ab, 2016abc; Buber, 2016; Engels, 2021; Lallement, 2009; Renault, 2016; Reichhart; 2019 Riot-Sarcey, 1998). Important figures such as Saint-Simon, Fourier or Owen aimed to bring together labour and ideals of emancipation. Their work revolved around a central question, phrased by Miguel Abensour as: “how to build association?” (2013a). Although utopian socialism has had radical, short-lived and often forgotten feminist influences (Taylor, 1993) as well as a matrimony now being highlighted (Fayolle & Matamoros, 2023; Lallement, 2019, 2022), political constructions of “what labour could become” remain shaped by these inherited “masters’ dreams” (Abensour, 2013a).

Furthermore, feminist critiques have challenged androcentric definitions of labour, broadening the field to include alternative theoretical frameworks such as social reproduction theory (Arruzza, 2016; Bhattacharya, 2017; Brenner & Laslett, 1991; Ferguson, 2019; Glenn, 1992; Vogel, 2013) and care work (Gilligan, 1983; hooks, 2018; Molinier, 2020; Tronto, 2013). Other currents, and Black feminist theories especially, have decentered the predominantly white, middle- and upper-class perspectives on labour, highlighting systems of oppression such as forced labour (Davis, 2019; Glenn, 1992; Morgan, 2004) and North/South dynamics (Parreñas, 2015; Khader, 2019). Other scholars have bought attention to unrecognised forms of labour, such as emotional labour (Durr & Harvey Wingfield, 2011; Hochschild, 2012; Illouz, 2007), unpaid collective work (Banks, 2020; Simonet, 2018), and forms of work that remain illegitimized (for ex. porn work, Berg, 2021). Despite these critical claims, the historical development of capitalism – with its persistently gendered and racialized division of labour – can be considered as dystopian – a “bad place” – that has led some feminist thinkers to reject the idea of equality in such a context (see for ex. Lonzi, 1974).

Utopia is often presented as stuck in contradictory meanings, between dismissing configurations of domination (negation) and proposing alternative forms of life (anticipation and imagination). Following Jacques Rancière, this contradiction can be overcome when thinking about utopia as a double-negation: the nonplace (utopia) of a nonplace (reality), where utopia-building is not about escaping reality but confronting it (2016). Recently, the uses of utopia in the social sciences have been disputed for its polarization between ideal and realistic theory, between “strong” and “weak” utopias, asking too much or too little (Chrostowska & Ingram, 2016; Levitas, 1990). A debate that was for example surpassed in sociology by Erik Olin Wright’s proposal to investigate “concrete utopias” (2010).

The conference will use utopia for its central function: “confronting the problem of power” through sidelining and introducing “a sense of doubt that shatters the obvious” (Ricoeur, 1986). While we firmly acknowledge the need for utopia in critical thinking (Stahl, 2023), we also underline the importance of multiple approaches to emancipatory politics as a compass for utopia-building (Allen, 2015). As a result, we will accept understandings of utopia both as a reflexive tool for critique and as a heuristic tool for transformation. Three complementary approaches to utopia-building can be considered: 1. reorganise labour; 2. redefine labour; 3. abolish labour.

1. Reorganise labour

Feminist utopia-building has focused on developing alternative ways of organising labour, reconfiguring the relation between the individual and the collective. Criticising the patriarchal and capitalist model of reproductive labour that cuts ties between “lesbians and women-identified women”, Audre Lorde theorised a politics of “interdependence of mutual (nondominant) differences”, allowing us to “return with true visions of our future” (2018). Other feminist scenarios encourage forms of cooperation and solidarity as alternative principles of social organisation, especially in the labour sphere, against individualism and competition (Cago, 2020; Federici, 2018; Harcourt, 2024; Mohanty, 2003; Salem, 2019).

Questions that arise include: what feminist utopian forms of labour re-organisation (including its negation) have been theorised or experimented to reconfigure social relations and values? To what extent do feminist utopian models of labour reorganisation redefine traditional gender roles and assignations? On what justifications have these discourses and/or experiments been contested? To what extent have they been developed at the expense of other social groups and/or led to the re-institutionalisation of power relations?

2. Redefine labour

Feminist critiques have subverted entrenched definitions of labour by proposing alternative moral values to those central to the capitalist system (Gilligan, 1983). In this respect, feminist utopias have imagined political configurations where social relations are governed by principles of nurturing, putting forward reproduction as a valued and central form of labour. Ethical perspectives of ecofeminism have depicted utopias where labour is recognized as a mutual activity to be carried out in harmony by humans, non-humans and nature (Cuomo, 1998). On the other hand, and in different frameworks, certain queer scholarships have contested the reproductive paradigm, including in the purpose of utopias as such (Muñoz, 2009).

Questions that arise include: in what ways have feminist utopias redefined labour and the frontiers that have been built by the capitalist value system: between work/leisure, private/public, free/waged, caring/utilitarian, human/non-human, dirty/clean rational/emotional…? To what extent can redefinitions of labour allow for collective emancipatory politics? How is the capitalist and androcentric labour order already confronted here and now in the multiple subversive redefinitions of labour developed in the daily exercise of work?

3. Abolish labour

Positing the end of work as a utopian horizon, Kathi Weeks argues against feminist currents that have implicitly encouraged a capitalist ethic of work (2011). Furthermore, 1970s feminist family abolitionism has been revisited, emphasizing how the institution of the family and reproductive labour is a central site for gender oppression and competition (Weeks, 2023; Lewis, 2022). Other proposals to reduce and redistribute reproductive labour have posited utopian post-work imaginaries especially through technology and the robotisation of the domestic sphere (Hester & Srnicek, 2023. For arguments against, see Fortunati, 2018). These feminist abolitionist imaginaries typically confront the dystopian emergence of the trad-wife figure and its embodiment of gender divisions and stereotypes, or masculinist ideals of the value of work.

Questions that arise include: how have feminist utopias defined and justified the abolition of labour in its multiple forms? To what extent and in what ways have they proposed alternatives to the capitalist work ethic? Conversely, how have work-centred utopias forgotten or exacerbated struggles arising from the gender order?

Submissions

The conference welcomes contributions in the social sciences and humanities (sociology, anthropology, critical theory, political and social theory, political science, philosophy etc.), whether on theory or experimental practices. Contributions will investigate the political content and implications of feminist utopias that rethink capitalist relations to labour understood broadly. We will also welcome contributions from a broader array of disciplines, including the literary, historical and economical fields.

Presentations can be given in English or in French.