Highlights of the “Feminist Utopias at Work” conference.

Highlights of the “Feminist Utopias at Work” conference.

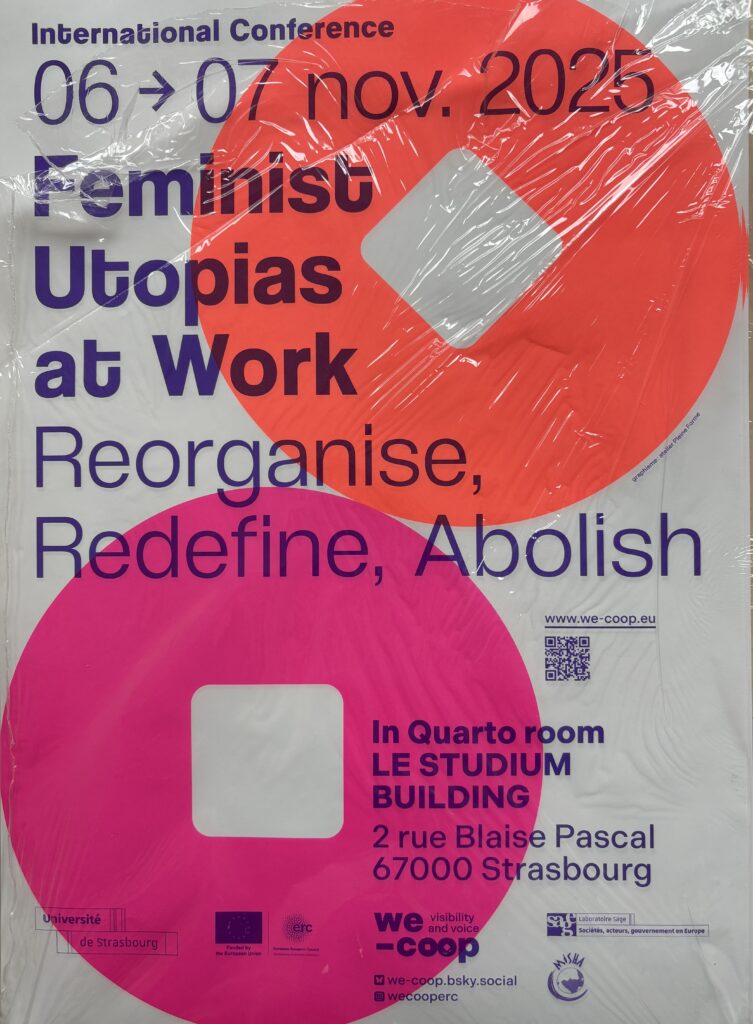

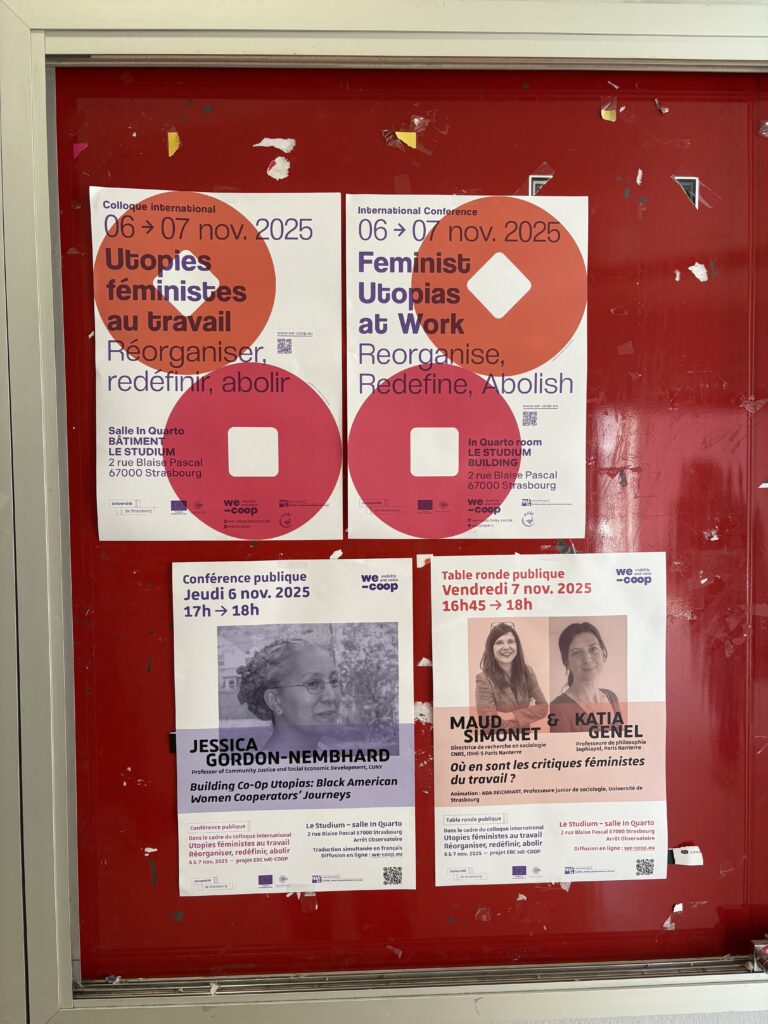

Goodies from the international conference “Feminist Utopias at Work“, University of Strasbourg, 6 & 7 November 2025. Thanks to Atelier Pleine Forme for the creative work!

Poster campaign in Strasbourg – over 30 sites for the “Feminist Utopias at Work: Reorganise, Redefine, Abolish” conference.

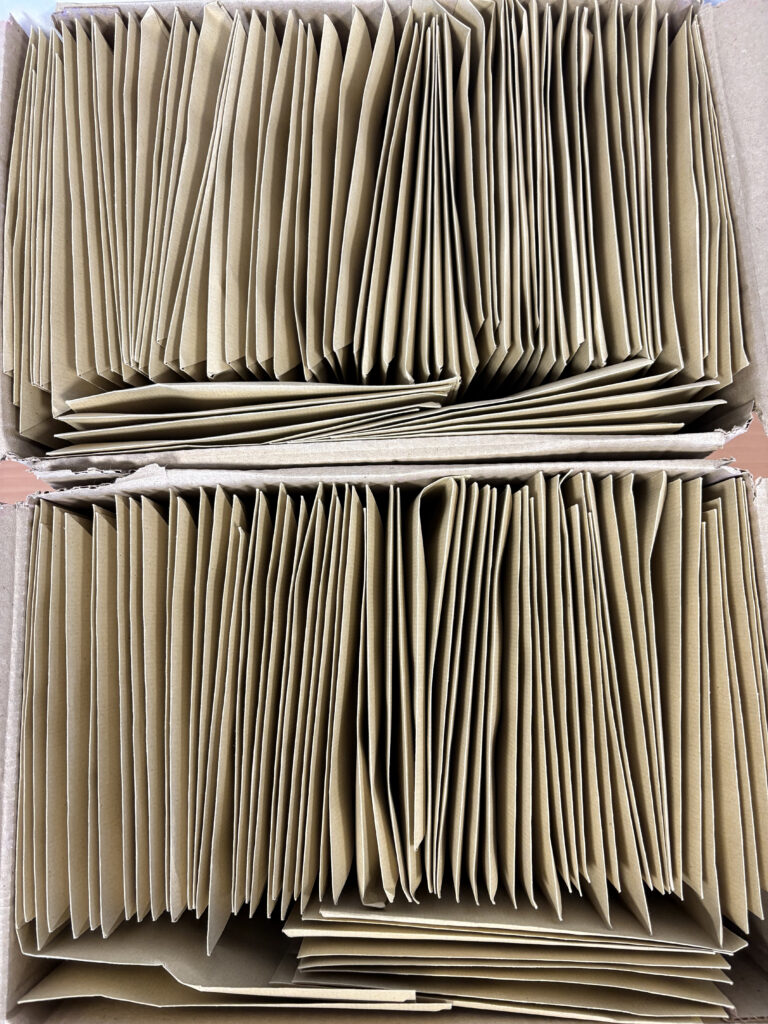

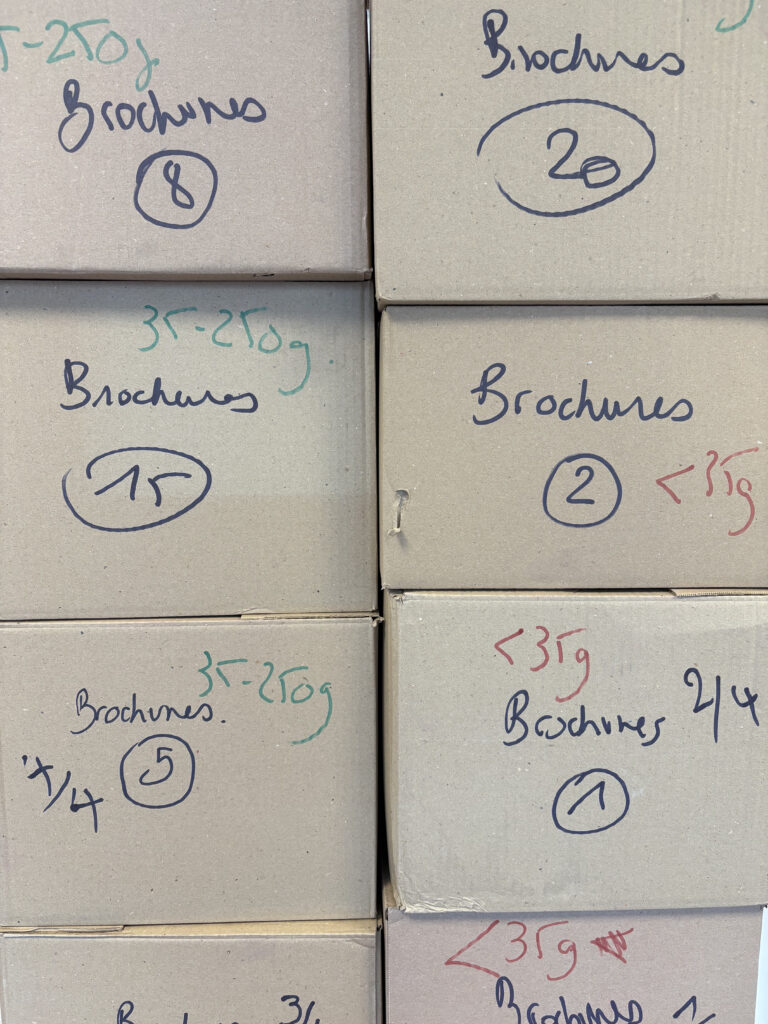

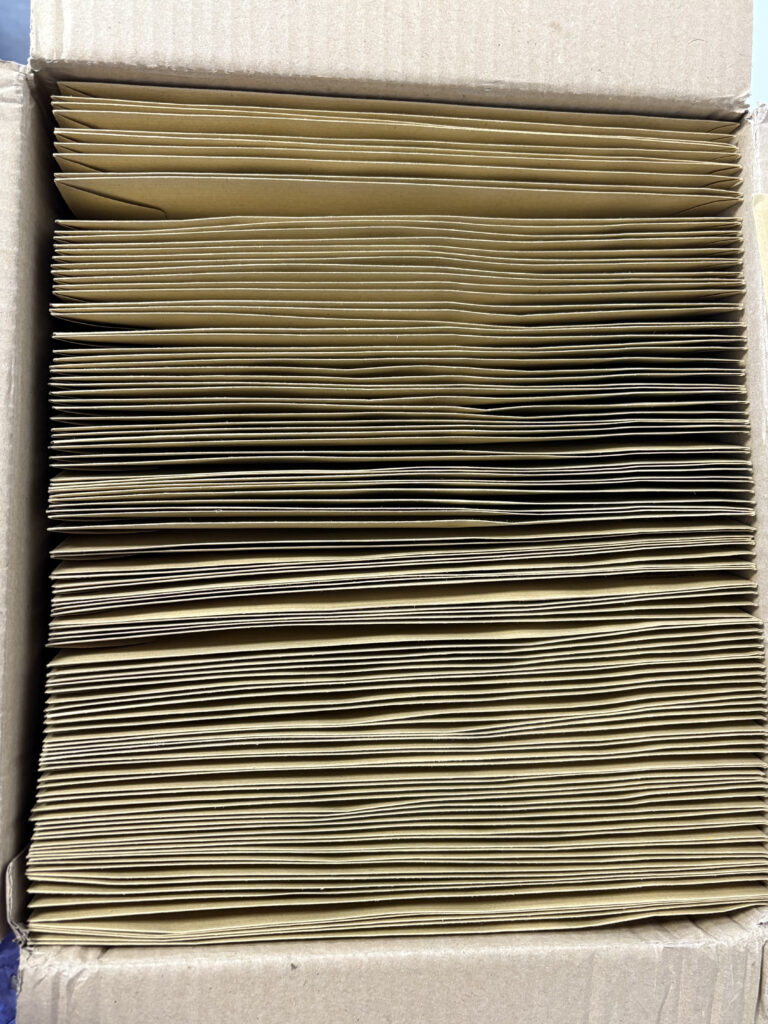

10,000 brochures for France’s worker cooperatives.

– Fanny Gouel – July 2025 – reading time: 7 minutes

In the French research community, the term “participatory research” is becoming increasingly common, whether in university laboratories, association offices, companies, or the public sector.

“Participatory research” (abbreviated to ‘PR’) [1] is part of a set of terms: “participatory action research” [2], “collaborative research” [3], “research and development” (R&D), “social survey”[2,4], “citizen science,” “participatory science,” “knowledge ecology” [5], etc.

However, even if these terms may be synonymous and therefore sometimes interchangeable, they also refer to a distinctly different positioning depending on who uses them and what is implied in terms of scientific approaches (epistemology* 1 ) and research practices (methodology* 2 ).

It is therefore worthwhile to explore the epistemological* question of what participatory research actually is, in all its plurality. This question also helps to clarify our specific approach within the WE-COOP research project.

Overall, participatory research refers to a survey that produces scientific knowledge with people concerned by the subject in question.

______________________________

In the social sciences, knowledge is situated in a social and historical context and therefore often comes within an interpretative paradigm* 3.

In other words, observations and analyses conducted in the real world (or “field” survey) are interpreted by researchers through comparisons, potential controversies, and reflective* 4 exchanges (i.e., reflecting on one’s own individual and collective position within the survey).

In participatory research, we can determine different degrees of participation from simple information sharing to collaboration for knowledge co-production.

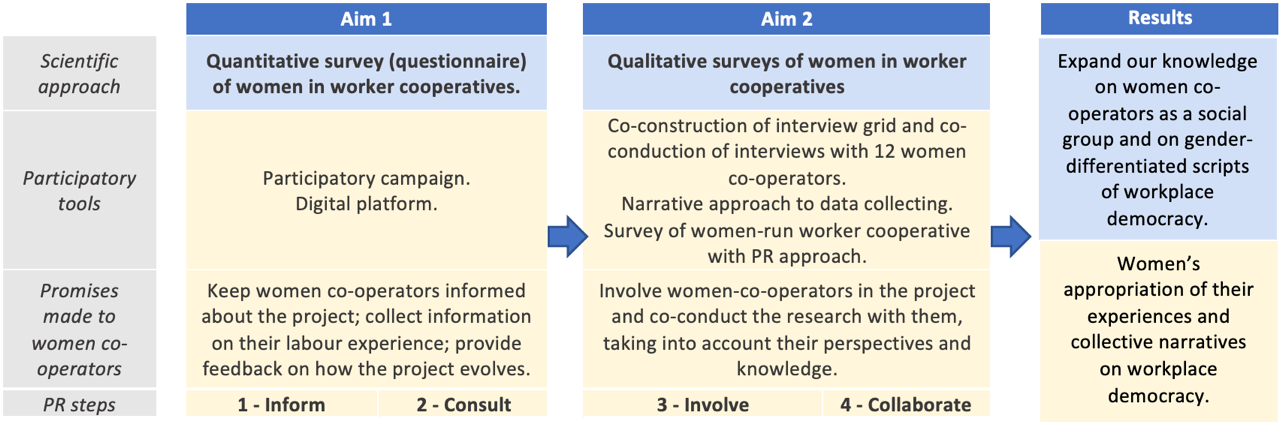

The WE-COOP project, for example, proposes four degrees of participation based on the scale developed by the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) [6] :

Transparency and information sharing regarding scientific research is the “0th level” of participation as well as the essential foundation for enabling the latter.

Those concerned by the research can thus follow its progress and ask questions or contact the research team if necessary.

The people concerned start to become “participants” when their opinions are collected to respond to certain needs of the scientific study.

This is the case, for example, when they are asked to participate in a research questionnaire.

This level of participation makes those involved more active in the research process. They are directly involved in the survey, meaning that they start to become part of the research team, and their opinions and experiences are listened to and considered in the survey design.

Finally, we truly engage in a process of knowledge co-production when there is collaboration between scientists (or professional researchers) and non-academic participants (or co-producers [3], lay researchers [1], researcher-actors [2]) who then work together within the investigation and where decisions are made jointly.

Furthermore, research refers to an entire process involving numerous stages, from choosing a topic to presenting the results.

Conducting collaborative participatory research throughout the entire project can therefore be very demanding.

In France today, it is hardly realistic to expect participants to invest as much time and effort as researchers in the entire research process. This is why researchers in Quebec, for example, prefer to use the term “research co-producers” rather than “co-researchers,” recognizing that participants cannot be involved in every stage of the research process. This is why researchers in Quebec, for example, prefer to use the term “research co-producers” rather than “co-researchers,” recognizing that participants cannot be involved in every “’minute detail” of the research, “from planning to funding” [3 p. 4]. This is an example of reflexivity* that allows them to become aware of the contours of their PR.

In short, the intensity of the degree of participation varies significantly depending on the constraints inherent in scientific research, as well as the vision and objectives expected of it.

Starting in the 1970’s, research collectives in various regions of the world, particularly in the Souths, called for “breaking the monopoly on knowledge production” [1].

In short, the criticism was that research is only produced within Western universities that pretend to have a neutral, objective, and therefore universal approach, while failing to invite a plurality of experiences within their walls. More specifically, they do not give a voice to structurally oppressed and/or marginalized groups such as women, indigenous peoples, non-white people, farmers, and workers.

This approach resonates with the “feminist standpoint epistemology* ” that began to be defended at the same time by thinkers starting with Dorothy Smith, then Sandra Harding, and Dona Haraway.

The latter stipulate that all knowledge is situated. Indeed, the perspectives of those who conduct scientific research are shaped by their social and political experiences. However, it is impossible to completely detach ourselves from our social condition. It is therefore preferable to be aware of this, to be reflexive, and to conduct research with a plurality of viewpoints. This approach allows for a better understanding of the subject and thus improves the production of knowledge while promoting its appropriation.

This is how “radical participatory research” [1] emerged.

The term “radical” highlights the aim to profoundly transform research by calling for a root change in power relations and ways of conceiving and conducting research. This is participatory research that is “bottom-up”, involving those primarily concerned and based on a desire for equality. Of course, they differ depending on the context, but they also seek to consider the experience as a whole, in other words, its sensitive, oral, and subjective aspects: this is referred to as “experiential knowledge” [3].

Finally, this research is deliberately “non-extractivist”. Unlike research that collects (or “extracts,” reminiscent of a colonial perspective) data from communities without providing anything in return or generating positive outcomes for them, this PR seeks to build mutual benefits and enable the production of useful knowledge according to and for the social groups concerned.

In summary, radical PR follows two concrete principles:

Thus, radical PR seeks to address not only scientific and ethical issues and concerns, but also political ones – as the second principle particularly demonstrates.

The WE-COOP research project is funded by an ERC Starting Grant (2023–28) from the European Research Council.

This type of funding requires that a research project be designed in advance in order to apply, and was therefore not co-constructed from the outset with those concerned by the study, namely the women members of French worker cooperatives (Scop).

Today, in the summer of 2025, there are three of us working full-time on the project. The WE-COOP team hopes to gradually expand and experiment with participatory research in four incremental stages. These stages were outlined in the introduction above and are highlighted in the table below:

Figure : Participatory research stages based on the International Association for Public Participation scale [6]. – WE-COOP project

This survey aims to collaborate with women cooperative members during the qualitative phase, which will begin in 2026.

It is hoped that “volunteer cooperators”, as they are currently called, will help develop the interview grid and co-conduct interviews.

This approach aims to answer questions raised directly by this social group, to horizontalize relations between the academic world and women workers in worker cooperatives, and to facilitate the appropriation by these workers of their stories and commitments.

We are already aware that even though travel expenses will be fully covered for cooperative members, not all of them will be able to participate for practical reasons (scheduling, money, etc.).

We must also be mindful of the risks of unpaid work, or in other words, ensure that participants do not feel exploited and keep their agency.

We want to move forward with the survey while being aware of its contours or limits and demonstrating reflexivity along the way.

As I write, we are in the quantitative phase (objective 1, see table) and a questionnaire is being distributed to women workers in cooperatives.

A consultative test phase involving around ten women cooperative members was organized to improve the questionnaire. Although the initial plan was to organize a convivial feedback session at the University of Strasbourg, this project was abandoned due to the testers’ lack of time, despite their motivation. The issue of time (combined with that of cost) then emerged, adding complexity to the implementation of a PR.

However, longer discussions were held with three of them, one by telephone and two over coffee. These responses were useful in improving the questionnaire and reflecting on difficult points in the survey, such as the question of official or “unspoken” hierarchy in cooperatives.

For anonymization reasons, the testers’ questionnaires were deleted—which is why the WE-COOP team did not want to expand the consultation group in order to maximize the number of responses for the actual survey. Finally, as of July 15, 2025, we have already collected more than 1,600 responses, far more than expected.

Thank you very much for reading this far!

We hope that this reflective note has helped to clarify what participatory research can be and to better understand our approach. There are still many elements to detail and discuss. If you have any questions, comments, experiences to share, or concerns, please feel free to write below (in the forum/comments section) and start a discussion.

[1] Godrie, Baptiste, Maïté Juan, et Marion Carrel. 2022. « Recherches participatives et épistémologies radicales : un état des lieux ». Participations 32 (1): 11‑50.

[2] Corsani, Antonella, 2020. Chapitre 5. L’enquête sociale comme co-recherche pour l’action. Dans : Chemins de la liberté Le travail entre hétéronomie et autonomie. Éditions du Croquant. p.147-186.

[3] Gervais, Myriam, Sandra Weber, et Caroline Caron. 2018. « Guide pour faire de la recherche féministe participative ». Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

[4] Lasida, Elena, Michel Renault, Marianne de Laat, et Bruno Tardieu. 2022. « Le savoir de l’expérience de la pauvreté. Étude à partir d’une recherche participative sur « les dimensions de la pauvreté avec les premiers concernés » ». Participations 32 (1): 93‑125.

[5] Santos, Boaventura de Sousa, João Arriscado Nunes, Maria Paula Meneses, et Isabelle Mullet-Blandin. 2022. « Ouvrir le canon du savoir et reconnaître la différence ». Participations 32 (1): 51‑91.

[6] International Association for Public Participation (IAP2). 2024. Spectrum of Public Participation.

https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/pillars/iap2_spectrum_2024.pdf

Presented by Ada Reichhart,

for the Handbook of Forgotten Institutions at the international conference on “Forgotten Institutions. Utopian Archives and Democratic Futures”,

organised by Sara Gebh, post-doctoral fellow in the ERC Research Project “Prefiguring Democratic Futures. Cultural and Theoretical Responses to the Crisis of Political Imagination” (principal investigator: Oliver Marchart).

When? 28th-30th November 2024

Where? University of Vienna, Austria

Paper given by Ada Reichhart,

at the “Ethnographies of Radical Democracy” conference,

organised by Federico Tarragoni (Prof. of Political Sociology – University of Caen/IUF), Pascale Devette (Ass. Prof. of Political Science – University of Montréal), Yohan Dubigeon (Ass. Prof. of Education Sciences – University of Saint Étienne), Audric Vitiello (Ass. Prof. of Political Science – University of Tours).

When? 6th-7th November 2024

Where? University of Caen, France

Paper given by Ada Reichhart,

at the conference on “The Meaning of Work” : Psychological, Social and Political implications of the Activity of Work.

When? 3rd-4th October 2024

Where? CNAM, Paris, France

Presented by Ada Reichhart,

at the “Gender(ed) Labor” conference,

organised by the Swiss Association for Gender Studies (SAGS).

When? 14th-15th September 2023

Where? University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

Paper given by Ada Reichhart,

at the “New Work – New Problems? Gender Perspectives on the Transformation of Work” conference, organised by the Gender Studies Committee of the Swiss Sociological Association and Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts (LUASA).

When? 7th-8th September 2023

Where? Luzern, Switzerland

https://www.hslu.ch/de-ch/soziale-arbeit/agenda/veranstaltungen/2023/09/07/new-work-2023